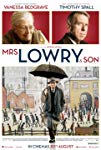

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Mrs Lowry & Son (2019) Film Review

Mrs Lowry & Son

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

When one looks back at the past few centuries of visual art, most of it can be seen clearly as an evolutionary process, one small innovation following another. even amongst the most acclaimed artists, few stand out for their originality like LS Lowry. A quiet man who insisted that he simply painted the world the way he saw it, Lowry created revolutionary images of working class life in industrial towns, exploring loneliness, anonymity and unexpected kinds of beauty. Adrian Noble's film draws on numerous accounts of the painter's life to explore what was probably the defining element within it: his relationship with his mother.

Vanessa Redgrave is almost unrecognisable as the sallow-faced, haggard old woman brought low as much by class-based angst as by any identifiable physical ailment. Experiencing digestive problems which she complains about at length, she is equally aggrieved by the ignominy of living in Pendlebury, in a terraced house whose lace curtains cannot keep out the screech of the siren at the nearby mill. She blames these reduced circumstances on her late husband, who incurred heavy debts whilst trying to keep her in the style to which she was accustomed, and she persistently reminds her son, Laurie (Timothy Spall) that they are middle class, innately better than the majority of their neighbours.

Making a modest living as a rent collector whilst providing her with ongoing personal care, Laurie is a disappointment to her, a fact that she is never slow to remind him of. She particularly disapproves of his 'hobby', his sneaking off up to the attic to paint. Within minutes of the film opening she is reading him a hostile and belittling review of one of his paintings written by a local art critic, relishing every word. He's bringing shame on her, she says. Won't he give it up? Won't he think, just for once, of her feelings?

Relationships involving this kind of dependency can be very hard to navigate in an emotionally healthy way, especially when they go on without change for many years, yet this one has reached such an extreme that the film verges on black comedy. Mrs Lowry never misses an opportunity to be cruel, and there's a sharp wit beneath her studiously befuddled exterior. The humour at play is often delightful yet at the same time one winces from the viciousness of her verbal blows. Laurie has no defence, only a seasoned stoicism. Will he endure this forever. Inevitably, the tension grows; yet there is something else at work here, something that transforms it all, as those already familiar with the painter's story will know: his abiding love for her.

The genius of writer Martyn Hesford lies in the way he uses this framework to explore the meaning and value of Lowry's art, gently teasing out the personality and the passions of a man who was never given to make speeches or discuss his work in depth. He couldn't ask for a better vehicle than Spall, who, five years after being named Best Actor at Cannes for his performance as Mr Turner, will once again be turning the heads of award voters. With most of the action taking place inside a single room, this is very much an actors' film, and the two leads are both on superb form.

How does one tell the story of an artist like Lowry from a visual perspective? The likes of At Eternity's Gate have done impressive work by adopting something of their subjects' own style. Noble's attempts to do that with Lowry are a bit hit and miss. Some of the staged outdoor scenes briefly resemble Wes Anderson tableaux, yet others move more naturally between realism and images famously captured by the artist's brush. In places realism is abandoned altogether and we see the artist move through a frozen crowd, examining faces in depth, an approach which gives us the time we need to identify what might have been obvious to him in a heartbeat. If you stick around at the end, there's a documentary sequence exploring a present day exhibition of Lowry's paintings.

Some might find this film overly indulgent and one wonders how well it will travel across the pond, with American viewers likely to be perplexed by the nuances of the English class system. As a portrait of two people trying to express their own humanity within roles they feel unable to escape, however, it is a powerful piece of work. There's a depth to Redgrave's performance which intermittently allows us to glimpse the mother as seen by the son, the human being trapped inside the monster; and the greater monster, the gestalt of poverty, guilt and mortal frailty, is never far from view. Mrs. Lowry And Son is by turns hilarious, brutal and tender, and like the best drama, it will leave you wondering what's going on behind the closed doors of all the other houses in Pendlebury and further afield. How many other geniuses have created art if lonely attics and, unlike Lowry, never succeeded in breaking through, never become the focus of films, doomed instead to exist as mere smudges of colour lost in a crowd?

Reviewed on: 30 Oct 2019